Dr. Heidi LM Jacobs is UWindsor’s Information Literacy Librarian.

For these reasons, when we at the library talk with students about information and research– what it is, how to approach it, what to look for and what to be cautious about– we talk about information literacy. Information literacy is, in its most basic definition, the ability to “recognize when information is needed along with the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” (American Library Association).

As you work with students doing research, you will likely be helping students navigate these kinds of information literacy components:

- Determining the extent of information needed (what kind of information does a student need to complete an assignment?)

- Accessing the needed information effectively and efficiently (how does a student find or retrieve that information?)

- Evaluating information and its sources critically (is this resource appropriate for the assignment? Is it reliable, current and authoritative?)

- Incorporating selected information into one’s knowledge base (how does this information work with other sources of information students have read or knowledge students already have?)

- Using information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose (how can students use the information to achieve the goals of the assignment?)

- Understanding the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information, and access and use information ethically and legally (how can students avoid plagiarism or copyright issues and cite their information properly?)

For many undergraduates, assignments that involve scholarly research are often overwhelming, confusing, and frustrating. As TAs and GAs you will often be the go-to person for undergraduate students’ questions and frustrations about research. Here are a few things to keep in mind.

- You are not on your own. Leddy Library has subject specialists who have expertise in your area of study and would be happy to meet with you to show you the best tools and resources for your students’ assignments. Meeting with your subject specialist at the beginning of the semester will prepare you for any questions you might encounter. You can also direct your students to your subject specialist.

- Your students are not on their own. Leddy Library has 2 Reference Help Centers and an Online Reference service staffed with friendly, helpful library staff who are well-trained to answer just about any question your students might have.

- We can come to you. We regularly come to classes and offer sessions on research strategies for specific assignments. If you or your professor would be interested in such a session, contact your subject specialist.

Thinking about information literacy in your work with students is important not only because it helps them with their academic work but because the critical thinking skills they develop will help them in the lives they lead outside of classrooms. As the UNESCO and IFLA written “Alexandria Proclamation” states,

“Information Literacy lies at the core of lifelong learning. It empowers people in all walks of life to seek, evaluate, use and create information effectively to achieve their personal, social, occupational and educational goals. It is a basic human right in a digital world and promotes social inclusion of all nations. Lifelong learning enables individuals, communities and nations to attain their goals and to take advantage of emerging opportunities in the evolving global environment for shared benefit. It assists them and their institutions to meet technological, economic and social challenges, to redress disadvantage and to advance the well being of all.”

When we talk with our students about research, we need to understand that by providing our students with opportunities to engage with information literacy, we are offering them opportunities to develop skills and capabilities that will have a wide-ranging impact on their learning and their lives.

Got a clever idea for a lesson? Maybe you’d like to sing or dance about this week’s topic? Why not mix it up with some costumes, music, and parody a popular song like these scientists at Zheng Lab?

credit: Zheng Lab – Bad Project (Lady Gaga parody), a submission for the Molecular and Human Genetics Retreat 2011 at Baylor College of Medicine.

Sharing resources you have created to improve your teaching is not always the easiest step to take. Often times we become very attached to the things we create that we think that others may not use the resource as we originally hoped. This can be a tricky situation especially if you work as a team, or very closely with others. How can you still be a good teamplayer without feeling worried about the fate of your original resources?

What is a ‘hard’ class? A hard class is any class students perceive as particularly distasteful or difficult, likely suspects include discipline specific required courses and discipline specific courses offered to non-majors. Often, these are classes the students have negative feelings about before the first day of class. They are said to be “pointless” or “incomprehensible” or just plain anxiety provoking. Assisting students in such classes can pose particular challenges for you as a GA/TA. If nothing else, they require you to be in good form. Students in these classes are more likely to come to your office hours, contact you with questions, and generally need more support than they would in other courses. The following suggestions are intended to help you assist students in these situations.

What is a ‘hard’ class? A hard class is any class students perceive as particularly distasteful or difficult, likely suspects include discipline specific required courses and discipline specific courses offered to non-majors. Often, these are classes the students have negative feelings about before the first day of class. They are said to be “pointless” or “incomprehensible” or just plain anxiety provoking. Assisting students in such classes can pose particular challenges for you as a GA/TA. If nothing else, they require you to be in good form. Students in these classes are more likely to come to your office hours, contact you with questions, and generally need more support than they would in other courses. The following suggestions are intended to help you assist students in these situations.

Understand your students

The first step to helping students succeed in hard classes is to understand where they’re coming from. As a GA/TA you are enviably positioned to help students learn without being responsible for all the administrative and institutional obligations shouldered by the instructor. While the instructor must balance empathy for students with a host of competing imperatives, you get to just be there for the students. Take advantage of this! Remember what it is like to be new at the higher education game? What were your anxieties (e.g. grades, exams, etc.)? What procedural stuff were you ignorant of then that seems so obvious now (e.g. paper formatting, citation, etc.)? Put yourself in the learner’s shoes.

Implementation

- Take a deep breath. Try not to get frustrated. Don’t get callous. Imagine yourself in their position and try to understand how they came to the decisions they did.

- Assess where your student is at. It is important to assess their incoming knowledge because it is possible they lack the basic building blocks that you are expecting them to have. Your explanation of new material won’t make a lot of sense if it presumes a non-existent grasp of ‘old’ material.

- Explain the logic of the subject. How do things fit together?

- Explain terms gratuitously. Students often find terms confusing because, when you’re learning, terms to do not immediately mean something in your head. You have to actually take time to think about what concept that word refers to (and they may be a little fuzzy on that anyway!). Because of this, using one term to explain another or to explain a process may leave learners mystified.

Respect your students

You are going to be busy. You are going to have your own anxieties and frustrations as a student. Sometimes it is difficult to treat the students we are assisting with adequate respect when we have our own lives and busy schedules. However, it is important to respect them as learners.

Implementation

- Help them understand why they are being asked to do something. Why do they have to cite that way? Why do they have to use a certain term in their response to get full marks?

- If you are actually teaching, for example a lab or tutorial, have a lesson plan. Every time. Do not wing it! What are the objectives for the time? How will you accomplish those objectives in the time given?

- For a clear, general lesson plan template, visit http://teaching.concordia.ca/resources/lesson-plan-template/ [editor’s note: see another great template in yesterday’s post on Lesson Planning]

- Answer emails promptly.

- Take adequate time to mark assignments and provide formative feedback. Formative feedback is feedback than can guide future practice, in other words, what changes they could make to perform better (Piccinin, 2003). This can be particularly hard to manage as marking takes a substantial amount of time. However, students learn more from formative feedback than from a mark. (It will also help you out when students challenge their grades. You will remember and be able to articulate why the assigned grade is appropriate.)

- Think about implementing a midterm GA evaluation, especially if you teach.

- Simply ask students to answer two questions.

- Which aspects of this lab/tutorial are working well?

- What specific changes would make this lab/tutorial more effective? (Kustra & Potter, 2008)

Help your students learn

Student learning is the outcome that justifies your pay. It is also a plus for you in your role as a GA/TA and as a fellow citizen or co-resident of those you’re assisting. If you help a student learn, they are less likely to request support as frequently as they would if they ‘just can’t seem to get it.’ In addition, this person will be more well educated and skilled as they move about the planet you share with them. Perhaps you even value learning as a good thing in and of itself. How, then, do we do this?

Implementation

- Confer with the instructor to make sure you are really clear on the quality criteria for an assignment when it is assigned, NOT when you are marking it. Quality criteria are the things (i.e. use of terminology, proper citation, etc) that must be in place for a student product (i.e. answer, participation, assignment) to be judged as being of a certain quality (i.e. mark) (Sadler, 2010). Communicate these quality criteria to students. If you are teaching, communicate criteria when assignments are handed out. Try showing an example of an answer with all the quality criteria present and another example that is missing some; this will help students concretely recognize what criteria look like. It is also helpful to mention criteria when teaching relevant concepts. Whether or not you are teaching, you can provide this information when students email you, even if they don’t ask for it.

- Use accessible analogies and examples. People learn new things by making associations with things they already know.

- Try wording explanations multiple ways and repeating them, particularly for concepts that are difficult for students.

- If you teach, try to be high energy. They don’t have good feelings about this class and probably don’t want to be here. Try to keep them with you and don’t let their disaffection drag the energy level down. That only results in increased inattention and thus less learning.

- Tell students about additional resources for learning support. Many students are not aware of the resources that are available.

- University of Windsor Academic Data Centre, University of Windsor Academic Writing Centre, a good citation website (such as those linked through the Leddy homepage under “Writing Help”), etc.

References

Kustra, E.D.H., & Potter, M.K. (2008). Leading Effective Discussions. London: Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education.

Piccinin, S.J. (2003). Feedback: Key to learning. London: Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education.

Sadler, D.R. (2010). Beyond feedback: Developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 535-550.

Piccinin

“The written feedback provided should give students guidance to improve their performance on subsequent summative assessments.” P. 33

“Formative feedback flows from assessment activities with the exclusive aim of providing information that allows people to learn something about their knowledge, skills, or attitudes and to make a change and ultimately improve their learning.” P. 17

I love lesson planning. But if you would have asked me how I felt about lesson planning during my first semester teaching as a graduate instructor, I would have responded with “Aarrgh!” or an equivalent sentiment. How much time do I allot for each activity? What if I talk to much? What if I don’t talk enough? What if we run out of things to do before the end of class time? These were only a sample of the questions that plagued me. Luckily, I had a very supportive supervisor who took the time to offer loads of advice into preparing a good lesson plan. His insights got me through the first two weeks or so of classes, until I could find my lesson planning groove, and the Centre for Teaching and Learning.

I love lesson planning. But if you would have asked me how I felt about lesson planning during my first semester teaching as a graduate instructor, I would have responded with “Aarrgh!” or an equivalent sentiment. How much time do I allot for each activity? What if I talk to much? What if I don’t talk enough? What if we run out of things to do before the end of class time? These were only a sample of the questions that plagued me. Luckily, I had a very supportive supervisor who took the time to offer loads of advice into preparing a good lesson plan. His insights got me through the first two weeks or so of classes, until I could find my lesson planning groove, and the Centre for Teaching and Learning. Want to know a secret? You can improve your teaching by talking to, watching, and adopting techniques from other teachers. Want to know where to find these other teachers who are also interested in talking about, watching, and adopting teaching techniques? Try a workshop at your Centre for Teaching and Learning.

Want to know a secret? You can improve your teaching by talking to, watching, and adopting techniques from other teachers. Want to know where to find these other teachers who are also interested in talking about, watching, and adopting teaching techniques? Try a workshop at your Centre for Teaching and Learning.

The University of Windsor has several coming up this semester including Group Work, Instructional Skills, Lecturing and Presentations, Using CLEW, and Online Education. Check out the entire list here. GAs and TAs are always welcome.

How can you be prepared when you walk into the classroom? What can you do ahead of time so that the class runs smoothly? Besides making yourself familiar with the content, preparing open-ended discussion questions or a learning activity to get everyone engaging with the material?

One of the most important things you can prepare — the thing that will help everything else fall into place — is knowing the goal of the class. The course itself will have learning outcomes somewhere prominent on the syllabus, but has the instructor included clear learning outcomes for each lesson? Quite likely the answer is no. There may be a posted topic, but that’s not the same thing.

Ask yourself what new knowledge, skill, or understanding students should walk away with at the end of the hour (or whatever time you have with them). What specifically do they need to get from today’s lesson? Once you’ve figured this out (in clear, concise language) you can share the expected learning outcome with your class. They’ll know what they’re supposed to be learning — and so will you. You’ll know how your lesson should end and once you have an ending, you only need to build a path to that conclusion.

Having a clear objective can help you focus your information or weed out tangential information. Any participatory activity will have a point — because you planned it with a goal.

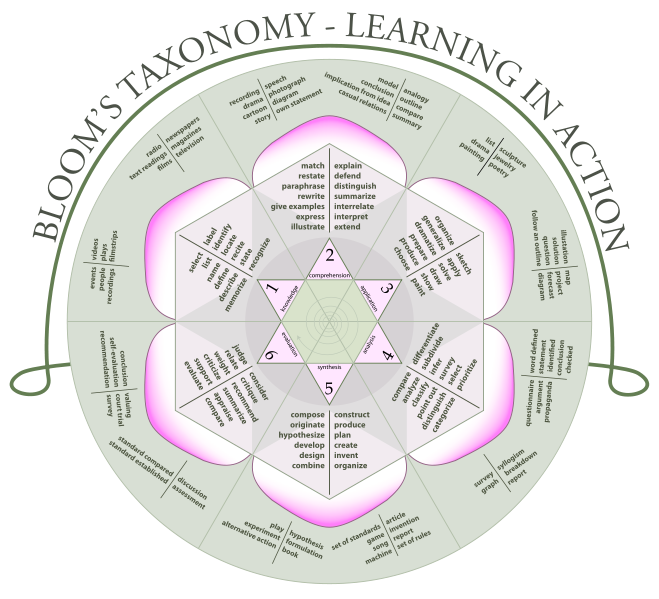

Learning outcomes should be measurable and there are tools out there to help you with this. Bloom’s Taxonomy is one (and you can see it below. Click to see large). Sometimes it’s pictured as a rose, as shown here and sometimes it’s shown as a pyramid. Depending on what type of learning you’re trying to encourage, there are suggested verbs for writing your learning outcomes. Have a look – and then go write some learning outcomes! (Would love to see some in the comments!)

A friend posted a status update on Facebook yesterday, calling himself the worst TA ever.

What could make someone think that?

Actually, it’s not that hard to imagine. There are a lot of things that make us think we should do better. It’s part of academia – we want to be good at things. Thing is, we all have bad days. And as academics, we’re trained in analysis (and meta-analysis). It’s hard not to be critical of yourself, but it is possible to examine the situation and learn from it. Even tenured faculty who’ve been teaching *forever* have bad days. (Shhh! they don’t want anyone to know!)

It could have been any number of things that got my friend down: things forgotten (like lesson plans), a classroom experiment that didn’t work out, a group that wouldn’t talk, a class where no one came prepared. Sometimes we get frustrated and act with (ahem) very strong emotions… It happens. It will be okay. You are not the worst TA ever.

If the goal is to become a better teacher, there are things you can do to make that happen. Reading about teaching and learning is one thing you can do; taking advantage of workshops in your campus Centre for Teaching and Learning is another. Asking more experienced teachers who are good at what they do can also help.

What other steps can a person take to take to make better teaching a reality?

Recent Comments